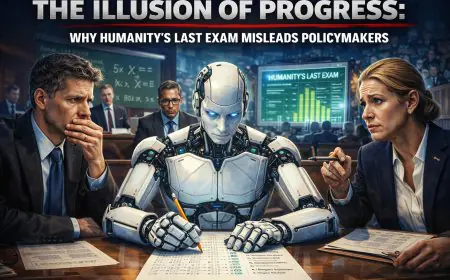

The Illusion of progress: why Humanity's Last exam Misleads Policymakers.

As AI models begin to "pass" the world’s most difficult benchmark, Humanity's Last Exam (HLE), experts warn of a dangerous disconnect. This article explores why high scores on PhD-level trivia are creating a false sense of security among regulators and why academic benchmarks are a poor proxy for real-world AI safety and governance.

The Benchmark Trap: High Scores vs. Real-World Capability

In the high-stakes corridors of Washington D.C. and Brussels, a single acronym is currently dominating the conversation on artificial intelligence: HLE. Short for Humanity's Last Exam, this benchmark was designed to be the ultimate finish line for AI—a collection of over 3,000 questions so complex that only human subject-matter experts with PhDs could solve them. As we move through 2026, and as frontier models from Google, OpenAI, and Anthropic begin to post scores exceeding 50% accuracy, a narrative of "near-AGI" has taken hold among policymakers.

However, many of the world’s leading AI researchers are sounding the alarm. They argue that HLE is providing an "illusion of progress." While the numbers on the dashboard look impressive, they may be fundamentally misleading the very people responsible for drafting AI safety legislation. The core issue? Being a "genius" at answering obscure academic trivia does not equate to being safe, reliable, or ethical in a real-world environment.

The Goodhart’s Law Problem

At the heart of the debate is Goodhart’s Law: "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure." Because HLE has become the primary metric for "intelligence," AI labs are now optimizing their models specifically to pass it. This leads to a phenomenon known as "benchmark contamination," where models are trained on data that looks suspiciously like the exam questions themselves.

For a policymaker, seeing a model score a 60% on PhD-level chemistry is a signal that the AI is ready to assist in drug discovery. In reality, the model may simply be a "stochastic parrot" that has memorized the patterns of high-level scientific discourse without understanding the underlying physical constraints. When these models are deployed in the real world, they often fail at simple "intern-level" tasks—like basic project management or cross-referencing conflicting data—that HLE simply doesn't measure.

Why Policymakers are Misinterpreting the Data

Legislators often look for clear "thresholds" to trigger regulation. If an AI passes a certain intelligence test, it might be classified as "High Risk" under frameworks like the EU AI Act. The danger of HLE is that it encourages a binary view of AI capability. If a model passes "Humanity's Last Exam," the assumption is that it has reached a level of General Intelligence.

This is a dangerous fallacy for several reasons:

- Lack of Agency: HLE measures static knowledge, not "agency." An AI can know the answer to a quantum physics question but still be unable to autonomously book a flight or spot a phishing email.

- The Safety Paradox: A smarter model is not a safer model. In fact, high-intelligence models can be more effective at bypasses, social engineering, and generating sophisticated misinformation—risks that HLE is not designed to track.

- False Competence: Policymakers may be tempted to deregulate "low-intelligence" models that fail HLE, even though those models might still be capable of large-scale algorithmic bias in hiring or lending.

As noted by researchers at FutureHouse, the current trend of "benchmark chasing" is pulling resources away from evaluative science. We are building models that can pass tests, rather than models that can solve problems.

The Shift Toward Agentic Benchmarks

To avoid being misled by the "illusion of progress," the next generation of AI governance must move beyond academic exams. Experts are now calling for a shift toward Agentic Benchmarks. These tests don't ask the AI for a multiple-choice answer; they give the AI a goal—like "organize a research conference" or "debug this 10,000-line codebase"—and measure its success in a sandbox environment.

According to reports from Scale AI’s SEAL Leaderboards, models that score highly on academic tests often struggle when their "agency" is put to the test. For regulators, this is the metric that matters. The threat or benefit of AI comes from what it does, not what it knows.

Conclusion: Redefining "Progress" for 2026

Humanity's Last Exam was a useful experiment in testing the limits of LLM knowledge, but in 2026, its role in policymaking has become a liability. If we continue to treat PhD-level trivia as the benchmark for "safety" or "human-level capability," we will remain blind to the real-world vulnerabilities of autonomous systems. It is time for regulators to look past the scorecards and start measuring the impact, agency, and accountability of the agents we are inviting into our society.